Options Magazine, Summer 2021: A burgeoning collaboration is exploring how to balance complex tensions over land use and other interlinked environmental issues.

As a vast and remarkably diverse archipelago of more than 17,000 islands, and the world’s fourth most populous country, Indonesia faces very complex environmental questions.

“The urgency of addressing climate change, sustainable land use, and inclusive development were apparent to the government, but conventional approaches seemed to not be working,” says Yos Sunitiyoso of the Bandung Institute of Technology in Jakarta, Secretary of Indonesia’s IIASA National Member Organization. “Systems analysis is ideally suited to tackle such interlinked challenges, which led Indonesia to join IIASA in 2012. There were high expectations that IIASA could help us develop solutions to the pressing issues around sustainable development.”

Chief among these issues is forest management. Indonesia holds more than 100,000 km2 of tropical rainforest, behind only Brazil and the Democratic Republic of Congo; and agriculture is the main source of income for a large and growing population. Inevitably, this creates a clash over land use. Much natural forest has been replaced with palm oil plantations and other farmland, and there are many areas of burned forest and land in various states of abandonment or degradation.

The RESTORE+project

RESTORE+ is a project using systems analysis to reveal the trade-offs between economy and ecology.

“Our aim is to move beyond the simplistic argument: “conserve forest” vs. “exploit forest”,” says IIASA researcher Ping Yowargana. “We need a higher-quality discussion, acknowledging both economic pressure and value in conservation.”

The project is mapping vegetation across the country, then modeling how restoration options could affect crop yields, carbon stocks, and biodiversity, and finally using that to project the outcome of different policy scenarios. When discussions with stakeholders began, it became clear that this process would not be simple.

“It was natural for us to start by saying, let’s identify where degraded areas are, then see what we can do,” says Yowargana. “But our stakeholders would respond, ‘that is an oil plantation generating income for the people, why do you call it degraded?’ So we abandoned the concept of degraded land. Instead, we make maps of restoration potential. This involves classifying land cover into 10 categories, such as agroforestry, rubber monoculture, and logged forest (also known as secondary forest).”

The mapping project uses crowdsourcing. A platform called Urundata displays satellite images and asks people to classify land cover. Workshops with Indonesian remote-sensing experts provide insights into more sophisticated image interpretation. Results from both Urundata and the workshops inform an algorithm, which generates detailed land-cover maps of Indonesia.

Stakeholder input has also led to a more inclusive list of restoration options, including commercial options, such as agroforestry with oil palms, as well as reforesting with natural vegetation.

The final stage of the project will be to model various future scenarios. One focuses on conciliatory approaches such as agroforestry, another on strong policy enforcement. Other scenarios explore restoration using market-based mechanisms. The IIASA GLOBIOM model, tailored to Indonesia, will project outcomes for the economy, land cover, and climate. These policy scenarios result from a back-and-forth dialogue with the Ministry of National Development Planning, part of their close collaboration with IIASA. Early stages of RESTORE+ informed the Ministry’s 2017 Low Carbon Development Initiative report, which set a national agenda for green development.

“The challenges the ministry gave us were a great lesson in policy-science interaction: what’s important is not only what the scientists think is important,” says Florian Kraxner, IIASA Agriculture, Forestry, and Ecosystem Services Research Group Leader.

“Our mission initially sounded simple – the “science to policy” household mantra of IIASA – but it turned out to be challenging in many ways, in managing the project, engaging people, and ensuring that insights from that engagement inform the different streams of research,” adds Yowargana.

The lessons learned should however keep providing value after the final report, in Indonesia and elsewhere.

“We have developed a suite of methods that can be picked up and improved,” says Kraxner.

Several Indonesian institutions were crucial in the collaboration. World Agroforestry Centre Indonesia provided maps, an agroforestry systems model, and expert knowledge; WWF Indonesia mobilized the crowdsourcing effort; and World Resources Institute Indonesia designed and conducted stakeholder workshops, and built the Urundata platform.

“They took the generic IIASA idea and made it work in a complex and specific national context,” notes Kraxner.

“We have many experiences where international research collaboration is relatively one-sided, with only limited roles for Indonesian researchers,” concludes Sunitiyoso. “RESTORE+ is a good example of how ideas from Indonesia were reciprocated in a joint activity.”

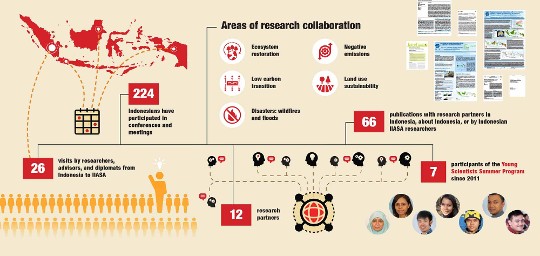

International modeling collaborations centered on Indonesia

Other collaborations are tackling air quality, sustainable cities, resilience to natural disasters, water and energy issues.

For example, Indonesia has great potential for hydropower. Researchers from China and IIASA collaborated on a study of how climate change could affect hydropower on the island of Sumatra, accounting for the physical effects on river discharge, and the economics of installing and managing infrastructure. The study, performed with the IIASA BeWhere model, found that under a 1.5°C warming scenario, hydropower production increases to the point where it can cut 40 million tonnes of CO2 from emissions – but under 2°C that drops to only 10 million tonnes. If warming therefore goes too far, it hampers efforts to mitigate climate change.

An IIASA collaboration with the Institute for Global Environmental Strategies (Japan) looked at approaches for treating wastewater from the fish processing industry. Using the GAINS model to assess different technologies and governance options, the study showed that some wastewater treatment approaches would generate considerable methane and carbon dioxide emissions. "By exploring different trade-offs, it is possible to identify the option delivering the maximum benefits for both climate and water,” says IIASA researcher Adriana Gómez-Sanabria.

By Stephen Battersby