Does COVID-19 affect men and women differently? Tomas Sobotka sheds light on the demographics of the coronavirus pandemic in Europe.

A question from a Time magazine article has a clear underlying message: “Why is COVID-19 striking men harder than women?” By now, everyone has learned that men are more vulnerable to COVID-19 and, if infected, they tend to die much more often than women.

Are men however also more likely to get infected? On the face of it, the number of infections by gender suggests an almost perfect gender equality. Women represent on average 47% of all infections in 70 countries reporting the number of cases by sex, as listed in the online data tracker by Global Health 5050.

Case settled? Not quite yet. The aggregated total number might be deceiving. To understand an underlying story, one has to dig into the age and sex components of total infections. The overall balance of COVID cases by gender is an outcome of age- and sex-specific patterns of infection rates and the actual age- and sex composition of the population. This in turn, is often gender-unequal, especially at older ages, due to excess mortality among men and higher longevity of women.

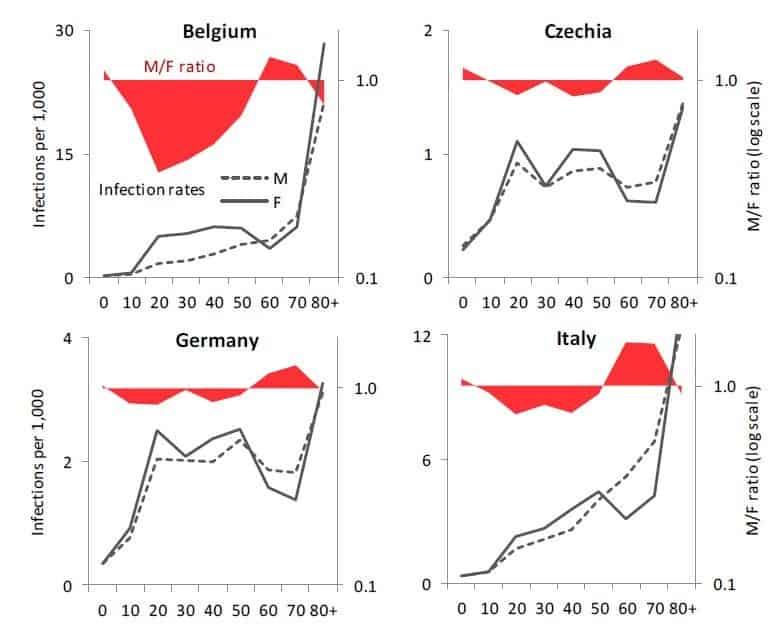

In fact, in ten European countries I examined with colleagues from the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital, including Raya Muttarak from the IIASA World Population Program, it turns out that infection rates are highly gendered, especially when looking at the age pattern of coronavirus infection. From the teenage years up until their late 50s, women are more likely than men to be infected with COVID-19. Women in their 20s display the biggest gender gap in infections: on average only 64 men were infected per 100 infected women aged 20-29. After age 60, the pattern reverses, as infection rates among women drop at age 60-69 and the male infection rates go up or stay stable. This crossover is also clearly visible in the charts for Belgium, Czechia, Germany, and Italy. Between ages 60 and 79, men are more likely than women to be infected. The imbalance is sharpest among people in their 70s, with an average of 136 infected males per 100 infected women. This puts older males at a double disadvantage: they are more likely to be infected and, once infected, they are much more likely to die (with both higher age and being a male identified as important risk factors).

Is our evidence credible? Clearly, many infections are undetected and our data are affected by different testing availability and testing priorities across countries. It is possible that women of working age get more frequently tested than men as women tend to be more concerned about their health. This would bias the estimated share of infected women upwards. However, the remarkable regularity in the age- and gender-pattern of infections in the analyzed countries suggests that the observed gender disparities are real. The same gender disparity by age is observed in Czechia, Denmark, Germany, and Norway with relatively few infections, as well as in Belgium, England, Italy, and Spain with high numbers of reported infections. Of course, countries differ in their gender imbalance, especially at younger ages: the gender gap is, well, gaping, in Belgium, which reports only 34 infected men per 100 infected women at age 20-29. It is much smaller in Czechia, Germany, and Norway, but the female dominance at young ages and the male dominance at older ages, with a crossover around age 60, is consistently found in each society we studied.

What’s the likely explanation? At younger ages, the smoking gun points at women’s employment and occupations. Most women of working age in Europe are employed. This may also partly explain why European countries actually register a higher number of infections among women than most other countries, with an average share of 55%. More importantly, women are often working in professions that are most exposed to the infection. Think of nurses, medical doctors, other healthcare professionals, but also all the care workers in retirement homes, which turned out in some countries to be the focal points of infection. The switch in gender balance occurs right around the retirement age. The higher likelihood of infection among older men is probably linked with their poorer health and lower immunity.

If employment is potentially risky for women, staying at home with children—itself a product of ingrained gender inequalities in work and care—may lead to fewer infections. In countries where women’s employment dips after age 30 due to their extensive parental leaves, infection rates often show a distinct dip after that age as well, going up again in their 40s: Czechia, Germany, and partly Norway and Switzerland show such an M-shaped pattern of infection rates among women.

Even though the fatality rates of women below age 60 are low, engagement in care-work poses a higher risk to healthcare workers and care-home staff. This factor should be included in the ongoing discussions on the impact of COVID-19 on women’s health and wellbeing.

© IIASA

© IIASA

This blogpost is based on the following paper:

Sobotka T, Brzozowska Z, Muttarak R, Zeman K, & di Lego V (2020). Age, gender and COVID-19 infections. medRxiv 2020.05.24.20111765. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.24.20111765

References

Global Health 5050. COVID-19 sex-disaggregated data tracker. https://globalhealth5050.org/covid19/ (accessed May 18, 2020)

Ducharme J. Why Is COVID-19 Striking Men Harder Than Women? Time, 1 May 2020. https://time.com/5829202/covid-19-gender-differences/

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.