The global COVID-19 crisis is challenging the social fabric of countries and communities across the globe. Interventions such as lockdowns, social distancing measures, and economic stimulus packages have been introduced to reinforce societal resilience. The resilience of national health systems is particularly in the spotlight – primarily keeping occupancy numbers of intensive care beds under a critical threshold, as well as improving access to basic health services for people infected with the virus, and ensuring that infections do not spread further.

© piyushpriyanka|Unsplash

© piyushpriyanka|Unsplash

At the same time, many COVID-19 affected regions and communities are confronted with additional multiple threats, including disaster and climate risks like flooding. For example, South Asia will be facing the monsoon season soon, and cyclones have already ravaged islands in the Pacific. So the question becomes, how do we support communities in preparing for and building resilience to such compound events like disasters AND infectious diseases?

Resilience has emerged as a system-based concept that explains how systems respond to shocks. IIASA has a long history of conceptualizing and assessing resilience. In partnership with members of the Zurich Flood Resilience Alliance (ZFRA), IIASA has co-developed an innovative approach called the Flood Resilience Measurement for Communities (FRMC) that measures the various facets of what builds resilience against flood risk at community levels. The FRMC consists of a holistic framework and an indicator-based assessment tool. It measures resilience before and after disasters at the community level – where people feel the impacts acutely and work together to take action. We define resilience widely in terms of a systems-thinking and development-centric conceptualization: “The ability of a system, community or society to pursue its social, ecological and economic development and growth objectives, while managing its disaster risk over time in a mutually reinforcing way.”

The FRMC measures resilience across a number of indicators that are collected through humanitarian and development NGO Alliance partners in communities in Asia, Europe, Latin America, and North America. It provides vital information for decision makers by prioritizing the resilience-building measures most needed by a community. At community and higher decision-making levels, measuring resilience also provides a basis for improving the design of public or privately funded programs to strengthen disaster resilience.

One of the seven themes that has been defined as a key aspect from the FRMC systems thinking approach is “Life and Health”, which is also relevant when looking at COVID-19 and includes access to and availability of healthcare facilities; strategies to maintain or quickly resume interrupted healthcare services; safety knowledge and Water and Sanitation (WASH).

Insights into dealing with COVID-19

In a recent research paper we analyzed FRMC data collected in 118 communities across nine countries in Asia, Latin America, and the US and explored which capacities or capitals contribute most to community disaster resilience. We identified multiple interactions, for instance, how action on bolstering health also contributes to social capital. There are two takeaways from this research that are relevant to other compound events, including the COVID-19 pandemic.

First, fair and functioning health systems play a key role in building resilience against compound risk – against flood as well as against other stresses that lead to negative health outcomes. Strategies that enable interrupted health systems to quickly resume are critical, and need to be in place before a disaster strikes.

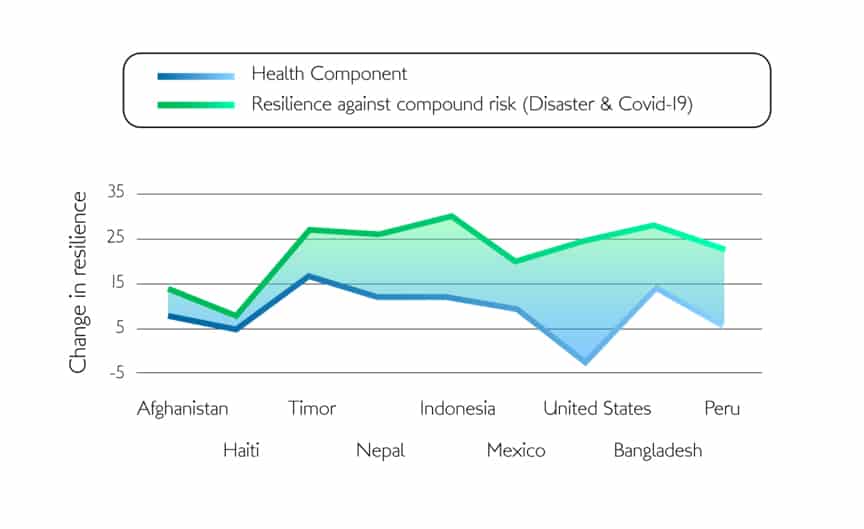

In the communities where ZFRA conducted FRMC studies, disaster resilience and the health component scored relatively low at the beginning. However, when interventions such as household health-related trainings in Mexico, or hospital capacity assessments in Nepal, were implemented (with our measurement tool running), the health component increased for almost all countries (except for the USA) (see blue line in Figure 1). As the health component is a key part of resilience it contributed to disaster resilience overall, including ‘compound risks’ (green line in Figure 1). This means that (further) accelerating investments into health services (e.g., as part of COVID-19 response and recovery packages) leads to additional benefits for other shocks.

© IIASA

© IIASA

A second takeaway is that through a so-called ‘multifunctionality’ effect, co-benefits are induced. This provides evidence of a virtuous cycle effect where higher resilient capacity in one area fosters communities’ resilience capacity for other functions. As community functions and outcomes are connected in a community system, improved access to health services can generate co-benefits (e.g., healthier individuals attain higher levels of livelihoods and build more social networks, which again build resilience during a shock). This has been well understood in the theoretical literature, and our analysis for the first time provides needed evidence at community level for flood and disaster risk.

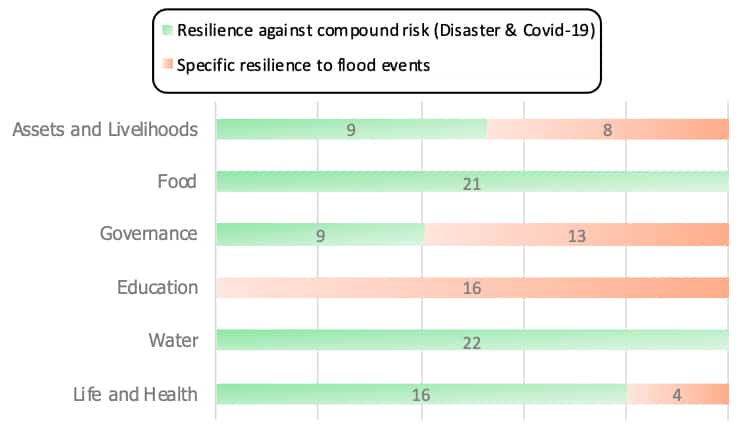

If these co-benefit effects are taken into account, we find evidence that Food and Water strategies (see Figure 2) can be most efficient in building resilience to both adverse flood and health events. In fact, our sources of resilience indicate that the capacity in the Food and Water dimensions also foster health resilience.

Risk awareness is hazard-specific but can be integrated into packages that tackle risk generally. For example, health relevant interventions for infectious diseases (e.g., appropriate hygiene measures) can be integrated into flood evacuation plans. A best-practice example from our work are the campaigns and fairs carried out in Mexico and Nepal targeting educational awareness on health-related impacts during flood events.

© IIASA

© IIASA

There is growing recognition by researchers, policymakers, and practitioners of the need to address compound risks in a development-centric way, tackling multiple threats with a focus on human wellbeing, rather than on hazards only. The COVID-19 crisis calls for donors, national governments, civil society, and communities to invest in comprehensive approaches that create multiple benefits.

Our system-based resilience research shows that using a systems resilience assessment at community level can identify direct short- and longer-term benefits. Investing in capacities builds resilience against compound risk such as flooding and infectious diseases. Investment into programs that ramp up health systems and WASH creates multiple benefits in terms of tackling COVID-19 and disaster and climate risks simultaneously. In the context of the upcoming monsoon and hurricane season, this means COVID-19 response and recovery packages need to invest in measures that also reduce social and economic impacts from COVID-19 under flood hazards. Additionally, diversifying household income strategies is high among the measures that unlock multiple co-benefits against compound risks. As action on COVID-19 (hopefully) moves from crisis response to recovery, such measures should be part and parcel of a post-COVID-19 recovery process, reducing the risk of vulnerable groups falling into poverty traps.

References:

Laurien, F., Hochrainer-Stigler, S., Keating, A., Campbell, K., Mechler, R., & Czajkowski, J. (2020). A typology of community flood resilience. Regional Environmental Change, 20(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10113-020-01593-x

Keating, A., Campbell, K., Mechler, R., Magnuszewski, P., Mochizuki, J., Liu, W., Szoenyi, M., McQuistan, C. (2016). Disaster resilience: What it is and how it can engender a meaningful change in development policy. Development Policy Review 35 (1): 65-91

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.