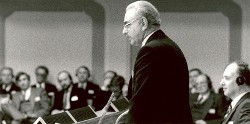

IIASA's first director Howard Raiffa on the negotiations that led to IIASA's creation.

© IIASA

© IIASA

The following edited transcript of a talk Raiffa gave at IIASA on 23 September 1992 describes how it all began.

The IIASA charter was signed in London in October 1972, but the history goes back six years earlier. In 1966 American president Lyndon Johnson gave a rather remarkable speech — in the middle of the Cold War — in which he said it was time that the scientists of the United States and the Soviet Union worked together on problems other than military and space matters, on problems that plagued all advanced societies, like energy, our oceans, the environment, health. And he called for a liaison between the scientists of East and West.

Johnson enlisted McGeorge Bundy, former adviser to presidents Kennedy and Johnson, to pursue the topic. One of the first things he did was to commission a report from the Rand Corporation, which was written by Roger Levien, the second director of IIASA. The report gave the United States a green light to go ahead.

Bundy also met the late Jermen Gvishiani, the deputy minister of the Soviet State Committee on Science and Technology — and he was delighted with the reaction. Bundy and Gvishiani realized that if IIASA was going to be stable, it should be multilateral. On that basis, Gvishiani pushed for inclusion of the German Democratic Republic. This was embarrassing for the United States which didn’t recognize East Germany. Our first crisis. It was surmounted by deciding that the new institute would be nongovernmental. How lucky!

What that meant was not very clear because the intention was that governments would finance the center. For the USA it meant that the National Academy of Sciences got into the act. The money went from the National Science Foundation, which is governmental, to the academy, which is nongovernmental.

On a Saturday afternoon early in 1967 I got a call from Bundy at home, saying that he was in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and could he meet me the next day; he would like me to do some consulting. I said, "What kind of consulting?" He said, "It’s pro bono but it won’t take long...."

© IIASA

© IIASA

Academician Jermen Gvishiani, Chairman of the IIASA Council and Deputy Chairman of the State Committee for Science and Technology of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, one of IIASA’s founding fathers.

Opening moves

The work in 1967 and 1968 was all directed toward the first planning meeting in Sussex, England. This meeting was also to include the UK, Italy, and France; Poland and the GDR would be there, and one other country from Eastern Europe. At the last minute they decided on Bulgaria.

We worked long hours preparing the Sussex meeting. We started on a Saturday morning in June 1968 only to receive a cable the following Friday from the Soviet Union saying that the Soviet Union, Poland, and the GDR would not be attending because of a crisis over Berlin.

Remember, these negotiations went on during the Cold War, the time of the Vietnam war and the Czechoslovakian revolution, and still they culminated in the creation of IIASA. In my view, this is really remarkable.

We talked a little in Sussex about whether we should start an institute without the Soviets. The decision was that no one would take it seriously. So, we went home—we thought that was the end of it. Then in November of ’68 there was a communiqué from Gvishiani saying, "What’s happening? Why is there no more action?" No apology, incidentally.

The next meeting was held in June 1969 in Moscow. Nothing much was accomplished until Gvishiani, Bundy, and a few others went for a walk in the woods, and made three momentous decisions.

- It should be an English-language institute—a suggestion made by Gvishiani, which was remarkable.

- The director would be an American; the chair of the governing council from the Soviet Union

- The Institute would be in the UK, according to the then Chief Scientific Adviser to the UK government, Sir Solly Zuckerman.

Decline and resurrection

In the early 1970s a hundred Soviet diplomats were expelled from the UK, and relations between the two countries froze. It was the French who got us out of the doldrums with their rousing statements about the importance of the institute. They offered the headquarters of SHAPE (Supreme Headquarters Allied Powers in Europe) at Fontainebleau, vacated when SHAPE had moved to Belgium. Fontainebleau was gorgeous; lots of historical rooms and tapestries. But when we said, "Can we put up blackboards, install computers, make a library," the answer was "None. You have to keep everything as it is."

Academician Jermen Gvishiani, Chairman of the IIASA Council and Deputy Chairman of the State Committee for Science and Technology of the Council of Ministers of the USSR, one of IIASA’s founding fathers.

The French did resurrect the negotiations. Bundy telephoned US Secretary of State Henry Kissinger while I was in the room. They both thought that it would be politically embarrassing to have a Republican administration sign up with Bundy, a Democrat, as their representative. So, the chief US negotiator became Philip Handler, president of the National Academy of Sciences. I was the only one transferred from the Bundy team to the Handler team, being supposedly apolitical.

From 1970 to 1972 we wrote a charter. The USA, embarrassed at having a multilateral institute dealing with advanced industrialized societies without Japan, insisted that Japan be included. Sir Solly objected, saying, "If we have Japan, why not Canada or Australia?" We compromised: all three were invited, and Japan and Canada accepted.

There had to be balance between East and West, so we invited Hungary and Czechoslovakia. Then we found that Japan didn’t want in. I went to Japan, tried to twist arms and seemingly got nowhere. A month before the charter was signed, we got a cable asking: "Where does Japan send its money?"

Name games

I have a folder from 1968 referring to the International Center for the Study of Problems Common to Advanced Industrialized Societies. That name was decided in Sussex, when the Soviets weren’t there, and they objected: "What do you mean by advanced industrialized society?" We said, "Well, we’ll have a Center for Research of Common Problems." And they said, ‘What do you mean by common problems?" We said, "We’ll have a Center for Research." They asked: "Why research and not training?’ We replied, "We’ll have a Center for Study." They said, "Should it be a center or an institute? And, will it be written as center or centre?" That's when we all decided: "We’ll have an institute."

Names kept pouring out. Cybernetics was the favorite word for Eastern Europeans. Management science, operations research, policy analysis — all kinds of names, but there was an objection to every suggestion. In the 1960s I wrote a book called Applied Statistical Decision Theory, and everybody said, "What do you mean by applied statistical decision theory?" So I had an idea: let's call it the international institute for applied systems analysis, which deals with management and policies and the societal implications of science, because nobody will know what it means and then we'll have a clean slate.

Some of the key issues in the charter had to do with selection of scientists, the size of the institute, finances, clearance of publications, areas of research, and voting systems. One possible showstopper was the selection of scientists. The USA, the UK, and the Western Europeans were adamant that countries could not send scientists to IIASA without the directorate’s approval. A wise choice and I was delighted.

Gvishiani liked this idea, but he was under constraint back home. A compromise was worked out: the Soviets would submit long lists of names and the institute could select from the lists. If there was no one on the list to satisfy IIASA, the lists would be extended. It took maybe six months of intense debate to come to this compromise.

Negotiating a charter

We had in mind that the institute would start with 60 to 80 full-time-equivalent senior scientists. The idea was to grow to 100, maybe 200. The USA said that it would put up US$2 million a year and, if the experiment worked, would increase its contribution.

We made a fundamental error in thinking it would be easy to ratchet up the contribution. The people who were involved in creating the institute lost power and other groups came in. It was very hard to get another group to raise the funding. That was a terrible error.

We never expected the Soviets to match the $2 million from the United States, but they said they would — in convertible currency. So, the idea was to have a two-tiered system: a third from the Soviet Union, a third from the United States, and a third from the six other member countries.

When membership expanded to twelve, the new members had to put up the same amount as the original six in the second tier. East Germany insisted that they match the contributions of West Germany, and we ended up with Bulgaria paying the same amount of dues as Japan.

There was to be majority voting except on key issues, where the Soviets would essentially have veto power. To my knowledge, the only real vote by the IIASA Council was the location of the institute. All the other decisions were made by consensus of the quainter type: you talk, talk, talk, then you formulate something that everybody can sign off.

So, we spent years worrying about the delicacy of the voting system, and it was never used. I understand that’s the way with every charter: it’s a contingency plan if things fall apart. If things don’t fall apart, you don’t pay much attention to the charter.

We had a trivial issue that became not so trivial. The Soviets wanted to get rid of the phrase "advanced societies." The US State Department, for some reason, got hooked on the phrase and said that if we deleted it from the charter they would hold up funding. We did what I call creative obfuscation and came up with the term "modern societies." That negotiation, believe it or not, took six months. It was a really trivial issue.

In the closing months before the charter was signed, Sir Solly suggested that the best way to clarify legal points was to give it to some group that was not English-speaking, because they would be very particular about the language. So, they gave it to the Quai d’Orsay in France. The charter got a clean bill of health, except that the phrase "modern societies" was underlined: "What does this mean?" they asked. It took another three months to convince them that it was all right to leave it.

Choosing a home

Let’s go back to the location. First, we thought it would be in Britain. Then, when the Soviets were expelled from the UK, the alternative was SHAPE headquarters. But there were problems with that, so we decided to explore other possibilities. Austria got involved, and we also received invitations to settle in Italy, the Netherlands, and Switzerland.

The location committee — I happened to be on it — looked at SHAPE headquarters versus this dilapidated schloss in Laxenburg and said it was a close call. France came back and said, "If you don’t like SHAPE, we will build you a new institute in Lyon or Marseille." And we tilted toward France.

The Austrians sweetened their offer a little, and we went back and forth. Then the issue of tax exemption came up. France said, "There’s no problem because you will have an international treaty." The US State Department said, "Absolutely no treaty," because the German Democratic Republic was involved. So, Austria’s chances went way up.

© IIASA

© IIASA

The signing of the IIASA Charter in London in 1972.

Then France came back and said, "Look, we need a treaty to give you tax exemption, but we can have a treaty between Poland and Italy and then the rest of you can come along." The USA said "Fine," but West Germany said "Absolutely not" because a treaty would be implicit recognition of the GDR. The Germans wanted it in Austria rather than France.

At the time there were some trade negotiations going on between France and Germany, and France said, "We’ll sweeten the trade deal if you allow the institute in France." Germany said "Fine." It appeared that we were going to France and that I was going to be the director. I started studying French. This was in the summer of 1972.

The vote was to be taken in London in October. Two or three days before the meeting, the French ambassador went to the White House and asked for a postponement so that France could sweeten its offer —that’s how intense the negotiations were.

Around that time the National Academy of Sciences surveyed US scientists about whether they preferred Austria or France. It was close, but many of the scientists who preferred France would not go to Austria as a second choice. The problem was a perception of anti- Semitism in Austria. Some of the scientists in the USA, mainly Jewish scientists, expressed concern.

But Austria was clearly the right choice. Symbolically, it was fantastically appropriate. The reception that we got from Austrian President Rudolf Kirchschläger and Chancellor Bruno Kreisky and the facilities were absolutely right. Even the French agreed, years afterwards, that we made the right choice.

Setting an agenda

The issue of global modeling was very intense. Some people thought it was the main purpose of IIASA. Aurelio Peccei, who was president of the Club of Rome, was a strong advocate. So was the Canadian representative. But Lord Zuckerman insisted that there be nothing about global modeling in IIASA and he threatened to pull out The Royal Society. The enmity between Sir Solly and Peccei was very severe.

The compromise was that IIASA itself would not do any work on global modeling, but would host a series of conferences to review contributions to global modeling and document the results.

There was great controversy about the research program. The Eastern Europeans and some of the Western countries thought that the Council should have full control. Others argued that the Council should indicate broad areas of research but leave the details to the directorate.

Everybody agreed that there should be only three or four projects— you can’t have a small institute and lots of projects. We compromised on seven or eight and some were ultimately given benign neglect.

The USA insisted on a project on population. Gvishiani said, "It’s a terrific subject, but it’s going to cause trouble at home — it’s a capitalist problem, not a communist problem." So we stayed away from population.

In the early years every country reviewed IIASA’s program. After three years the Soviets had a review and said that the selection of projects was imbalanced because there was nothing on population. Gvishiani and I laughed, and we agreed that we should start a new project on food and agriculture and weave in problems of population. A creative compromise.

One of the big issues was the political relevance of research. There was a feeling that IIASA was an experiment in bringing people together from different countries and different ideological positions, so don’t rock the boat. In 1974 I proposed to the council that IIASA invite groups interested in the Law of the Sea to spend the summer at IIASA. IIASA scientists would be available to build models of, say, the economics of mining manganese nodules, but that idea was voted out as being too controversial and too political; today I think it would happen.

There was a lot of discussion about project-specific support. The feeling was that this sort of support shouldn’t be more than 25% of IIASA’s budget.

A big issue was the selection of scholars. Some said that we should get a cadre of career people. The decision was made that the norm would be appointments for one or two years, occasionally four or five years: no career appointments. We decided on a one-salary system for scientists, with salaries competitive for Italy, Germany, and France. I believe that solution was right but it was tough to administer.

When I came to Vienna I got a cool reception from the director general of UNIDO because IIASA was East—West oriented, and the UN North—South oriented. Later we became friends. He was an Egyptian, and he invited me to go to Cairo to see if he could replicate a national applied systems analysis institute. And he was interested in having Egypt become a member of IIASA.

At that time the feeling was that IIASA’s membership should grow to about 20. So, the compromise was that Israel and Egypt could enter jointly. I went to Israel and Egypt and got their agreement that, yes, they would enter and work together. This was remarkable: it was before Sadat went to Jerusalem. But at the last minute it didn’t work out — not because of Israel’s participation, but because the Soviet Union and Egypt had a falling out.

Start-up problems

At the beginning the Council transferred something like $200,000 to my personal bank account in Boston and I was given freedom to hire people and write checks. The trouble was that these checks had to be endorsed by Alex Letov, the deputy director. I was in the United States and Letov was in Moscow — it would take three weeks, if at all, to get a check for $50.

So, I opened a personal account and the Ford Foundation gave me a discretionary fund of $300,000. I would spend money without authorization and then go back to the council and say, "Did I do right or wrong?" And they said, "You did right." And I said, "Well, put the money back into the fund."

One of the things that I did at the beginning was buy the Holzhaus, the lodge, so that we could have some place to put scientists. Schloss Laxenburg was not fully restored until 1976, but we occupied most of it in 1973.

When the Austrian government was trying to sweeten their deal they offered an apartment for the director in the Altes Schloss. But when the time came, they said they didn’t realize that the Schloss was signed off by the Ministry of Education. They were embarrassed: Was there anything else they could do in lieu? And we said, "How about giving us an athletic complex?" They said, ‘Sure, in the park we will build you tennis courts and a swimming pool and a sauna.’

When the time came, the Austrian universities said, "Why are you building these facilities for IIASA and not for us." And they had to back out. Austria was not supposed to pay the first three years of dues, and because of this embarrassment they paid. So, it actually cost them a lot more.

We had some land in the park and it was not clear whether we were going to keep it. So, I used my discretionary fund to build some tennis courts, which sort of secured it for us.

At the signing ceremonies in London, Sir Solly opened by saying that scientists wouldn’t start working in Laxenburg before 1975. He was wrong: by 1975 we had a sparkling array of talent working on problems of energy, ecology, water resources, and methodology.

It was a remarkable time. I got all sorts of advice, mostly saying, "You’re an academic, you don’t know the ropes, you need seasoned administrators." I took gambles on a young group of secretary/administrators, and we fumbled along. In retrospect, I wouldn’t change a single appointment.