Options Magazine, Summer 2022: Before joining IIASA in 1980, Michael Thompson was a Himalayan mountaineer. Navigating risk in the mountains has influenced his research on risk theory, and environment and development in Nepal.

© Michael Thompson

© Michael Thompson

A few months prior to the 1970 British expedition to the South Face of Annapurna – one of the highest mountains in the world – Michael Thompson and the legendary mountaineer Don Whillans pitched their tent in "The Sanctuary": an impressive set of peaks that comprise the Annapurna massif. Every day, Whillans would scan the enormous wall of rock and ice before them through his binoculars.

"Mountains may look beautiful, quiet, and still," said Whillans, "but they're not; they are on the move all the time." Every now and then, the roar of an avalanche would pierce the silence, with countless blocks of ice crashing down the side of the mountain they hoped to climb. "People tell you that if you follow the rules, you will be okay," Whillans added, "but they're wrong."

Being able to understand and assess risk is an essential skill for any mountaineer who wishes to survive the altitude, the cold, and the avalanches. Thompson, now a senior researcher in the Equity and Justice Research Group of the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program, learnt this first-hand on that expedition to Annapurna and on the subsequent one to the South-West Face of Everest in 1975. However, he never imagined just how useful those experiences would prove later in his academic work.

© Chris Bonington

© Chris Bonington

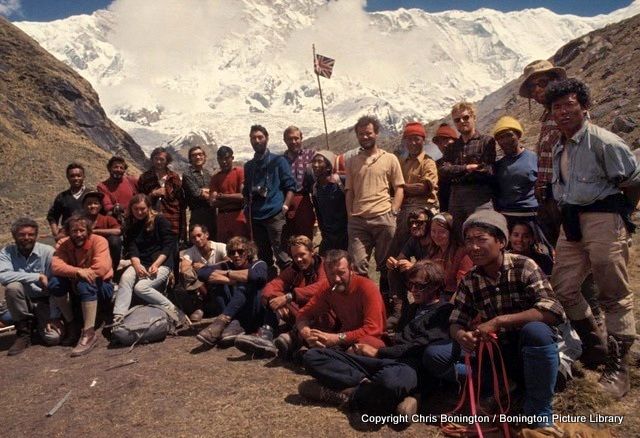

The 1970 Annapurna South Face expedition team pictured in front of the Annapurna massif. Fourth from the right in the first row is Michael Thompson, to his right is Don Whillans, with a cigarette.

Thompson studied social anthropology at University College London and then at Oxford before joining IIASA in 1980. His work at the institute took him back to the mountains: he developed a systems overview of the environmental and developmental problems of the Himalayan region for the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) and worked with Nepali researchers and entrepreneurs to bring novel technologies to light.

"To my surprise, mountaineering and applied systems analysis came together quite effectively," he notes.

He also drew on his experience of navigating risk in the mountains when he joined the lively debate on the different approaches to risk as part of the former IIASA Risk and Resilience Program.

"At that time, risk research was done as if it was chemistry; as if you could calculate the objective risk of everything. But it's not as simple as that," he explains. "People don't just react to risks; they react to what they perceive the risks to be."

Today, thanks in large part to researchers at IIASA, august bodies such as the US National Academy of Sciences and the UK's Royal Society recognize that, as Nature's correspondent put it, "public perceptions should be included in the assessment of risk."

By Fanni Daniella Szakal

Further info: