In his early years, IIASA researcher Michael Thompson was a Himalayan mountaineer. Navigating risk in the mountains has defined his view on risk more generally, thereby influencing his research on environment and development in Nepal.

© Chris Bonington

© Chris Bonington

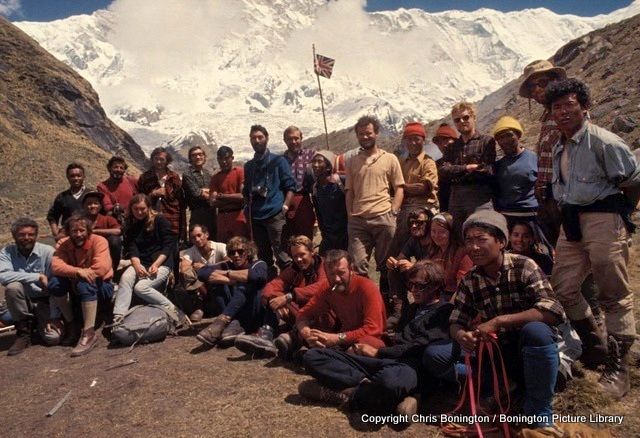

The 1970 Annapurna South Face expedition team pictured in front of the Annapurna massif. Fourth from the right in the first row is Michael Thompson, to his right is Don Whillans, with a cigarette.

A few months prior to the 1970 British expedition to the South Face of Annapurna – one of the highest mountains in the world – Michael Thompson and the legendary mountaineer Don Whillans pitched their tent in "The Sanctuary": an impressive set of peaks that comprise the Annapurna massif. Every day, Whillans would scan the enormous wall of rock and ice before them through his binoculars.

"Mountains may look beautiful, quiet, and still," said Whillans, "but they're not; they are on the move all the time." Every now and then, the roar of an avalanche would pierce the silence, with countless blocks of ice crashing down the side of the mountain they hoped to climb. "People tell you that if you follow the rules, you will be okay;" Whillans added, "but they're wrong."

© Michael Thompson

© Michael Thompson

Climbing 8,000-meter peaks is a death-defying tightrope walk towards historical achievements, so being able to understand and assess risk is an essential skill for any mountaineer who wishes to survive the altitude, the cold, and the avalanches. Thompson, now a senior researcher in the Equity and Justice Research Group of the IIASA Population and Just Societies Program, learnt this first-hand on that expedition to Annapurna and on the subsequent one to the South-West Face of Everest in 1975; both now regarded as among the greatest achievements in mountaineering. However, he never imagined just how useful those experiences would prove later in his academic work.

Environment and development in Nepal

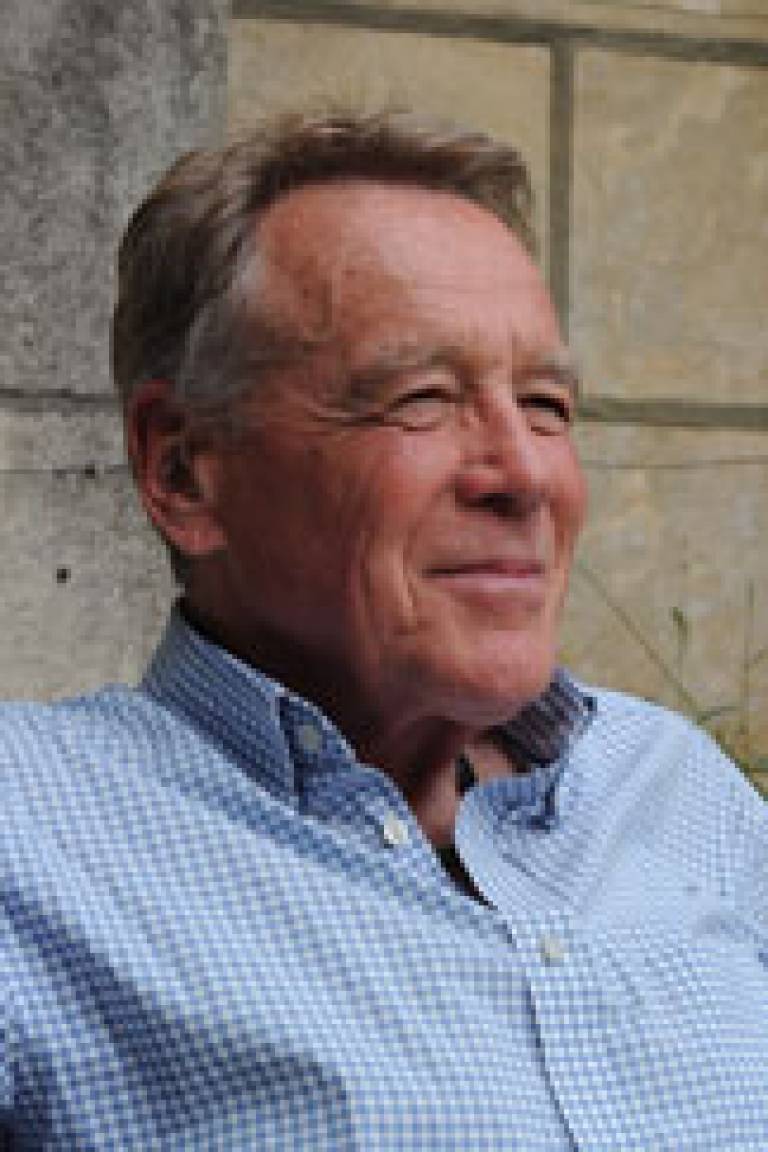

Thompson started rock-climbing as a child, escaping from boarding school on Sundays to let loose in the nearby mountains of the UK’s Lake District. After school, he trained as an army officer at Britain's Royal Military Academy Sandhurst, together with Chris Bonington, the leader of both those expeditions. "Neither of us were endowed with impressive military competence," says Thompson with a laugh, "but we did push the standard of climbing at Sandhurst higher than it had ever been." To the question as to how he went from climbing 20-meter rock faces to scaling the world's highest peaks, Thompson answers: "well, one thing led to another".

After leaving the army, Thompson studied social anthropology at University College London and then at Oxford. He has always been interested in people and in finding the social aspect of any problem. In 1980, he joined IIASA to work on environment, development, and risk. "Environmental and developmental issues are a tangled web of people and things, which is why you need applied systems analysis to untangle them and to understand what is going on," he explains.

© Michael Thompson

© Michael Thompson

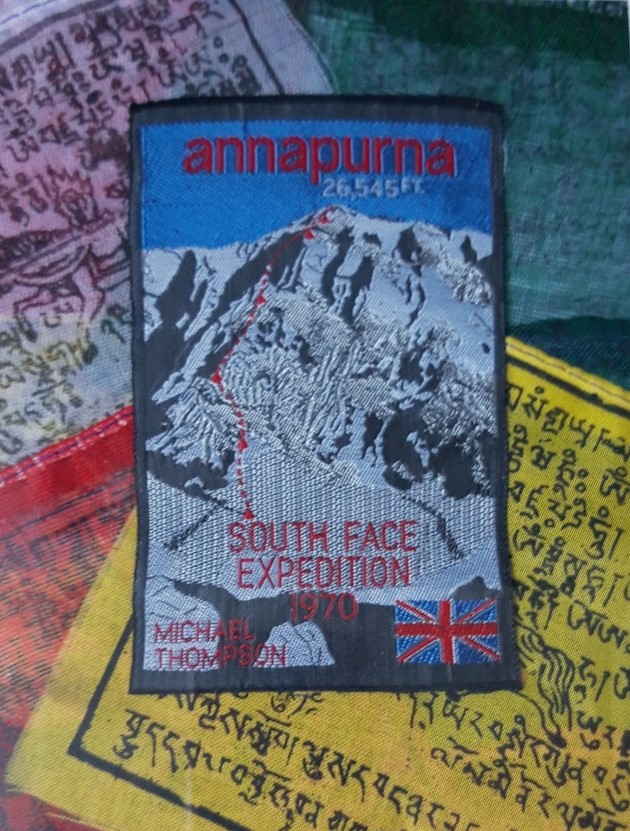

Embroidery in remembrance of the 1970 Annapurna expedition with Nepalese prayer flags.

When the United Nations Environment Program (UNEP) asked IIASA to provide a systems overview of the environmental and developmental problems of the Himalayan region, Thompson was quick to volunteer. His experience in Nepal and his contacts in the region enabled him to view things with a fresh eye, eventually publishing a report that up-ended the then-current environmental orthodoxy: the Theory of Himalayan Environmental Degradation. "To my surprise, mountaineering and applied systems analysis came together quite effectively," he notes.

Thompson has since worked with Nepali researchers and entrepreneurs on what are now called ‘innovation ecosystems’. Some of these novel technologies, such as low-tech electric vehicles, small-to-medium hydropower, and very small-scale biogas, have ended up being adopted in many countries around the world. A form of technology transfer, but not as envisaged by proponents of development assistance, who assume a one-way North-South flow.

The science of risk

As a member of the former IIASA Risk and Resilience Program, Thompson joined in the lively debate on the different approaches to risk. "At that time, risk research was done as if it was chemistry; as if you could calculate the objective risk of everything. But it's not as simple as that," he explains. "People don't just react to risks; they react to what they perceive the risks to be."

“Inevitably”, he stresses, “you are dealing with perceived risk, which is very different from pure objective risk.” His own view of risk was shaped by his past as a mountaineer – an activity that many people see as exhilarating, while for others it is far beyond the bounds of acceptability.

Thompson himself admits that he sometimes wonders just where he stands on that scale. "That I'm still around, I suppose, is a bit miraculous," he remarks. He survived an ice avalanche on Annapurna in 1970 when his expedition partner, who was just a couple of meters away from him at the time, did not.

"Following the rules still tends to be the standard approach in risk management, especially in what is called Disaster Risk Reduction: tick all the boxes provided by the experts and you'll be fine. But that's a long way from being right," Thompson adds, echoing what Don Whillans said more than fifty years ago in the Annapurna Sanctuary.

Even so, the understanding of risk is now more right than it was back in the days when everything was being reduced to objective risk. Thanks in large part to IIASA researchers, august bodies – such as Britain's Royal Society and the US National Academy of Science – now concede that, as "Nature's" correspondent put it, "public perceptions should be included in the assessment of risk."

Further reading:

* Chris Bonington (1971) "Annapurna South Face". London: Cassell.

* Chris Bonington (1976) "Everest The Hard Way". London: Hodder and Stoughton.

* Michael Thompson (1978) Out with the boys again. In Ken Wilson (ed) "The Games Climbers Play". London: Diadem Books. (344-353).

* Michael Thompson (1994) Climbing well treading softly. In Chris Bonington (ed) "Great Climbs: A Celebration of World Mountaineering". London: Mitchell Beazley. (210-213).

* Michael Thompson and Steve Rayner (1998) Risk and governance part 1: the discourses of climate change. "Government and Opposition" 33(2): 139-166.

* Michael Thompson, Steve Rayner and Steven Ney (1998) Risk and governance part 2: policy in a complex and plurally perceived world. "Government and Opposition" 33(3): 330-354.

* Michael Thompson, Michael Warburton and Tom Hatley (2007) "Uncertainty on a Himalayan Scale". Lalitpur, Nepal: Himal Books. (First published 1986. London: Ethnographica).

* Dipak Gyawali, Michael Thompson and Marco Verweij (eds)(2017) "Aid, Technology and Development: The Lessons From Nepal". Abingdon: Earthscan from Routledge.