Charlie Wilson and Elena Verdolini share insights and experiences from an expert workshop on the impacts of digitalization on energy, materials, the economy, markets, lifestyles, and society, and how these impacts directly or indirectly affect greenhouse gas emissions.

On 13-14 May, 35 scientists and industry representatives participated in an expert workshop on the impacts of digitalization on energy, materials, the economy, markets, lifestyles, and society, and how these impacts directly or indirectly affect greenhouse gas emissions. Hosted by the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) outside Vienna in Austria, the workshop was organized by a team from the 2D4D and iDODDLE projects, with additional support from the RCN-DEE, CircEUlar, and EDITS networks.

The workshop’s aims were to understand how both current and future trajectories of digital transformation impact emission-reduction efforts. This aim was motivated by the weak explicit consideration of digitalization in future scenarios and modeling assessments used to inform EU and global climate policy. This includes the thousands of scenarios reviewed in the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)’s recent 2022 assessment, few of which make any mention of digitalization as a transformative force shaping economic and social life.

The workshop took certain premises as common starting points. First, digitalization is a transformative and pervasive force creating both opportunities and risks for emission reductions across all sectors and domains. Second, digitalization comprises widely different technologies and applications from platforms and cloud computing to the internet of things and AI. Third, digital and climate governance need to be better integrated, in turn requiring joint scientific assessment of digital impacts on climate-relevant issues, and vice versa.

Day 1. Mapping digitalization impacts.

The workshop began with a series of impulse talks by experts to stimulate thinking on digitalization’s main impacts in four domains: energy and materials; society and behavior; economy and industry; and governance and markets. These four domains served as an organizing framework throughout the workshop.

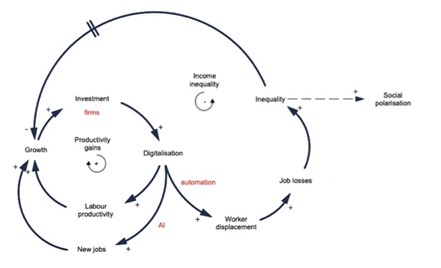

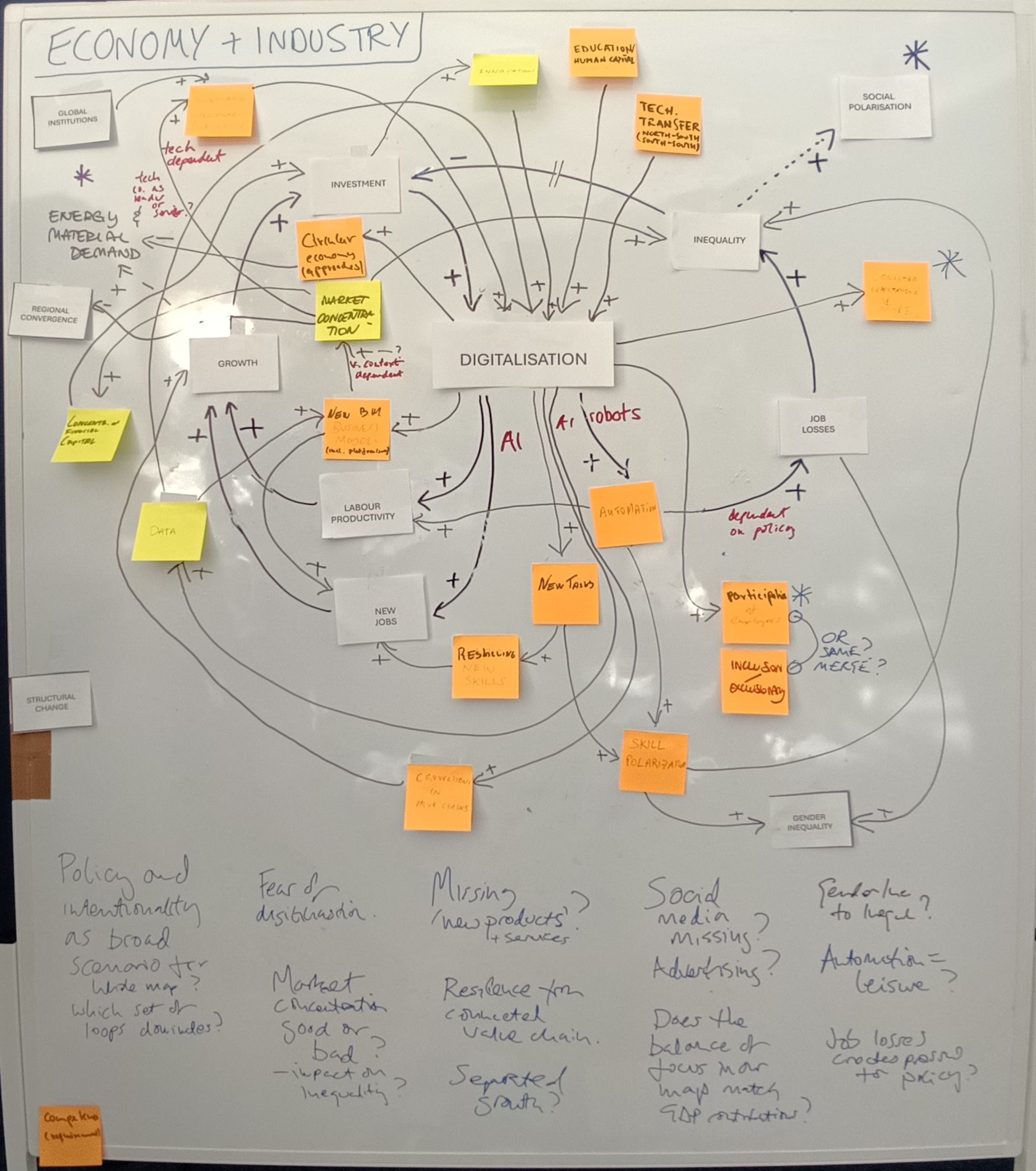

Participants then split into specialist breakout groups to map out digitalization impact pathways in each domain. Supported by facilitators, they used systems mapping techniques to identify dominant variables, causal relationships, and feedback loops, building on a basic concept model prepared in advance by the workshop organizers [Photo 2]. Impact pathways were then iteratively extended, discussed, and revised.

Photo 2. Digitalization impact pathways in economy and industry: initial concept model.

As an example, in the economy and industry domain [Photo 3], discussions centered around five main impact dynamics relating to: (1) labor productivity, growth, and investment; (2) skills and task displacement, job losses, and income inequality; (3) training and reskilling, and new job creation; (4) data, innovation, and new business models; (5) and firm competition, market concentration, and distribution of financial capital. Different digital technologies – with automation and AI as examples – activated these impact dynamics in different ways. Both were linked to productivity gains, and to skills and wage polarization: the former by displacing low-skilled, repetitive tasks; the latter by substituting higher skilled and more qualified workers.

After an initial round of systems mapping, participants had the opportunity to move between groups to help identify linkages between digitalization impacts across different domains.

In the governance and markets domain, for instance, participants discussed the role of social cohesion and trust in underpinning government effectiveness and strong climate governance. Digitalization could both strengthen social trust (e.g., through mechanisms of political participation) or undermine social trust (e.g., through misinformation). These impact dynamics linked to discussions in the society and behavior domain of how digital platforms and networks can serve to both mobilize and polarize, depending on how algorithms, influencers, big tech companies, and users interact.

The maps of impact pathways generated during the workshop were rich in insight, but complex [Photo 3]. The workshop organizers are now working on digitizing, cleaning, and organizing the maps to draw out more clearly the dominant positive (reinforcing) and negative (balancing) feedback loops in each domain. This is a steppingstone towards building an overall ‘meta-map’ integrating participants’ understanding of digitalization impact pathways that directly or indirectly affect greenhouse gas emissions.

Day 2. Part 1 - Exploring digitalization and climate futures.

The workshop continued with a series of impulse talks shifting gear from mapping digitalization’s current impacts to thinking through its future potential impacts under a range of assumptions.

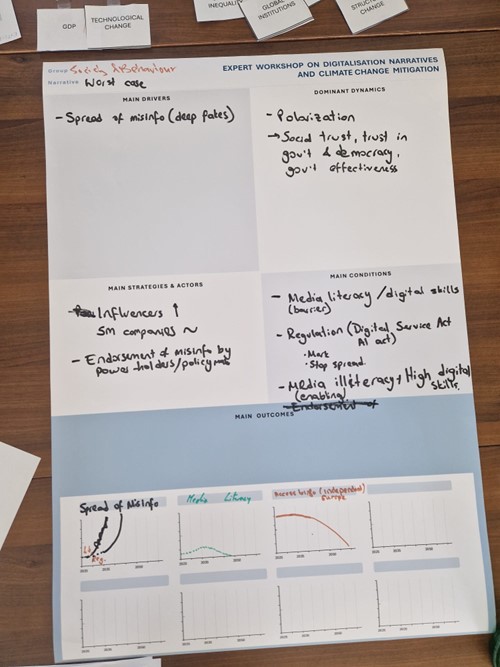

Back in the breakout groups per domain, participants used the systems maps to help characterize alternative possible digitalization futures. Facilitators tasked participants with exploring a wide future possibility space, bounded by best- and worst-case assumptions on which causal relationships or feedback loops dominated. Each future narrative was characterized by a set of drivers, dynamics, conditions, actor strategies, and outcomes [Photo 4].

As an example, in the society and behavior domain, participants focused on a worst-case scenario narrative in which the spread of misinformation causes a social polarization feedback loop to dominate, reducing social trust and government effectiveness. Influencers become increasingly powerful actors, including through use of deep fakes to undermine climate action. Media literacy and digital skills decline over the medium-term as they fade from school curricula. Availability of, and access to, information from independent sources becomes increasingly restricted.

Photo 4. Digitalization futures in society and behavior: worst case scenario.

As a different example, one group of participants focused on the tension between the extremely fast development and scaling of AI applications and their slower moving, longer-lived impacts on sustainability outcomes. In this ‘fast-slow’ digitalization scenario, advances in data and computation driven by strong consumer uptake and an AI arms race among big tech companies creates instability in the absence of an appropriate governance framework (‘AI for sustainability’) that extends well beyond the energy footprint of ICT infrastructure (‘sustainable AI’).

Characterizing alternative digitalization futures in this way helped identify salient uncertainties that could affect climate mitigation efforts. This set up the final workshop discussions on intervention strategies for aligning digitalization with climate goals over the near (to 2035) to medium-term (to 2050).

Continuing with the ‘fast-slow’ scenario narrative as an example, essential elements of the necessary governance framework include structures and capabilities for conducting rapid assessments, a cooperative leadership platform, and a focus on synergies between AI solutions and climate, equity, and justice.

Day 2. Part 2 - Digital and climate governance.

The workshop was designed to explore connections between digitalization impacts and climate outcomes to strengthen policy-relevant scenario and modeling analysis of these entwined issues. No consensus was sought on policy insights or messages. However, certain themes clearly emerged from different groups during the workshop discussions.

First, climate governance and policy have primary responsibility for driving emission reductions, including by ensuring market incentives are aligned towards low-carbon innovation, strategies, and business models.

Second, digitalization acts as an amplifier and accelerator of change, both for better and for worse. As the risks of adverse impacts are high, digitalization needs steering through governance to deliver societal value and avoid undermining climate goals.

Third, digital governance for climate mitigation can be narrow or broad. The narrow view argues that climate governance establishes direction; digital governance should ‘just’ tackle issues unique to the sector: (1) the energy and material footprint of expanding ICT infrastructure; and (2) societal risks for trust, agency, inequality, safety, and security.

The broad view argues that digital governance should additionally tackle the indirect impact of digital applications on greenhouse gas emissions through substitution, productivity, growth, rebound, and other effects evident at both micro and systems levels (e.g., from individual consumption choices on e-retail platforms to industry activity in automating or otherwise digitalizing production processes).

Fourth, both climate and digital governance are cross-cutting issues that require coherence and interaction between traditional policy departments, knowledge domains, and business objectives. Effective integration is a major challenge for skills, organizations, and assessments.

Fifth, AI was a cross-cutting theme throughout the workshop, particularly in relation to governance challenges as well as the considerable opportunities for highly diverse AI applications to support climate mitigation goals. Unlike climate governance, AI governance currently involves very few actors (firms and states). But both climate and AI governance depend on robust cooperative institutions, brokering, political agency, and the integration of justice and equity considerations.

A final roundtable set of recommendations for elements of a digital governance regime reflected this diversity of views among participants. Recommendations included the use of digitalization to monitor emissions, improve the quality of low-carbon services, shape consumer behavior, support agency and citizenship, boost social cohesion and trust in the state, and enhance the transparency of sustainability indicators.

The workshop organizers are now working on analyzing all the data collected; watch this space for a full workshop report!

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of the IIASA blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.