Shonali Pachauri discusses a new framework developed at IIASA to more accurately identify the energy poor.

© IIASA

© IIASA

Energy is a prerequisite for economic and social development. Today, it is widely believed that there are 840 million people still living without electricity in Africa and Asia, while many more are without access to reliable power. And because of COVID-19, this number is growing again.

But what if this data, which governments and donors rely on to allocate money and shape policy, are flawed? And what if we’re even further from eradicating energy poverty than we think? This is the conclusion of a new framework for counting energy access.

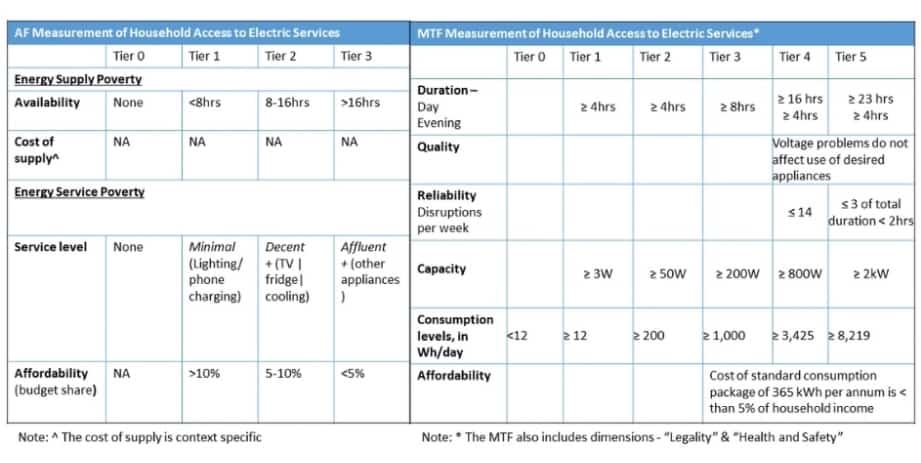

The United Nations uses a simple indicator of the share of population with electricity connections to measure energy access. But this grossly underestimates the number of energy poor, because it considers a household to have access even if they receive irregular quality and hours of electricity supply or are unable to afford anything beyond an electric light.

Recent efforts to improve how we measure energy poverty have made vast improvements but have now resulted in frameworks that are complicated and “data needy”, therefore difficult to scale up to a global level.

A new framework developed by IIASA builds on existing measurement frameworks, but simplifies and advances these to more accurately identify the energy poor. It has already been applied to actual data from Ethiopia, India, and Rwanda to test how well it captures energy poverty in comparison to the World Bank’s Multi-Tier Framework (MTF).

© IIASA

© IIASA

The framework distinguishes between two aspects of access: the quality of power supply and the circumstances of the end-user. This distinction is important to better direct policy efforts where they are most needed, that is, to energy suppliers and/or to households. It also reduces the number of dimensions and tiers to simplify the MTF.

Instead of correlating energy consumption with energy access, a key advancement of the new framework is using ownership of different types of appliances as a proxy for measuring household amenities and services derived from the use of these appliances to improve wellbeing. Electricity consumption is a misleading measure of energy service, because for those who use inefficient appliances, more consumption does not translate into more service. For instance, a household using six inefficient light bulbs is not better off than one that uses three efficient high luminosity light points and an efficient fan that provides comfort from the summer heat. The framework also improves on how affordability is measured to consider appliance purchase costs in addition to recurrent electricity expenditures in assessing the budget share spent on electric services.

When applied to real data, the framework suggests that the energy poor are more segmented than what is reflected by existing binary or MTF indicators. The categorization of households according to electricity consumption differs markedly from that according to energy services and using appliance ownership, revealing greater heterogeneity among the energy poor than what is reflected in the MTF’s consumption-based indicator.

In addition, the new framework shows that affordability is even more of a constraint to gaining access to modern electric services for households in Ethiopia, India, and Rwanda than reflected by the MTF. According to the MTF’s indicator of affordability, practically no one in Ethiopia or India would be considered unable to afford electricity access. However, if one includes the discounted cost of appliances needed to consume electricity in the indicator, about a third of the population in India and Ethiopia might be categorized as facing issues with affordability. In Rwanda, even without considering the discounted cost of appliances, most electricity consuming households are faced with affordability constraints to using basic electric services at home.

This evolution of measuring energy access is just a first step to more accurately counting the energy poor. This needs to go hand in hand with better data gathering, especially for countries and regions that face the biggest challenges in terms of extending access to modern energy services. Further refinements and applications of the framework can help improve how we identify the most vulnerable and design and target policies to achieve true energy access for all.

This blog post was first published on the PowerForAll Energy policy website. Read the original article here.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the Nexus blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.