Co-production is a term that has been cropping up more and more in discussions about public involvement and is fast becoming an integral feature of many research processes and proposals. Susanne Hanger-Kopp explains why not every project can or should include elements of co-production and how to make the most of such processes when they are used.

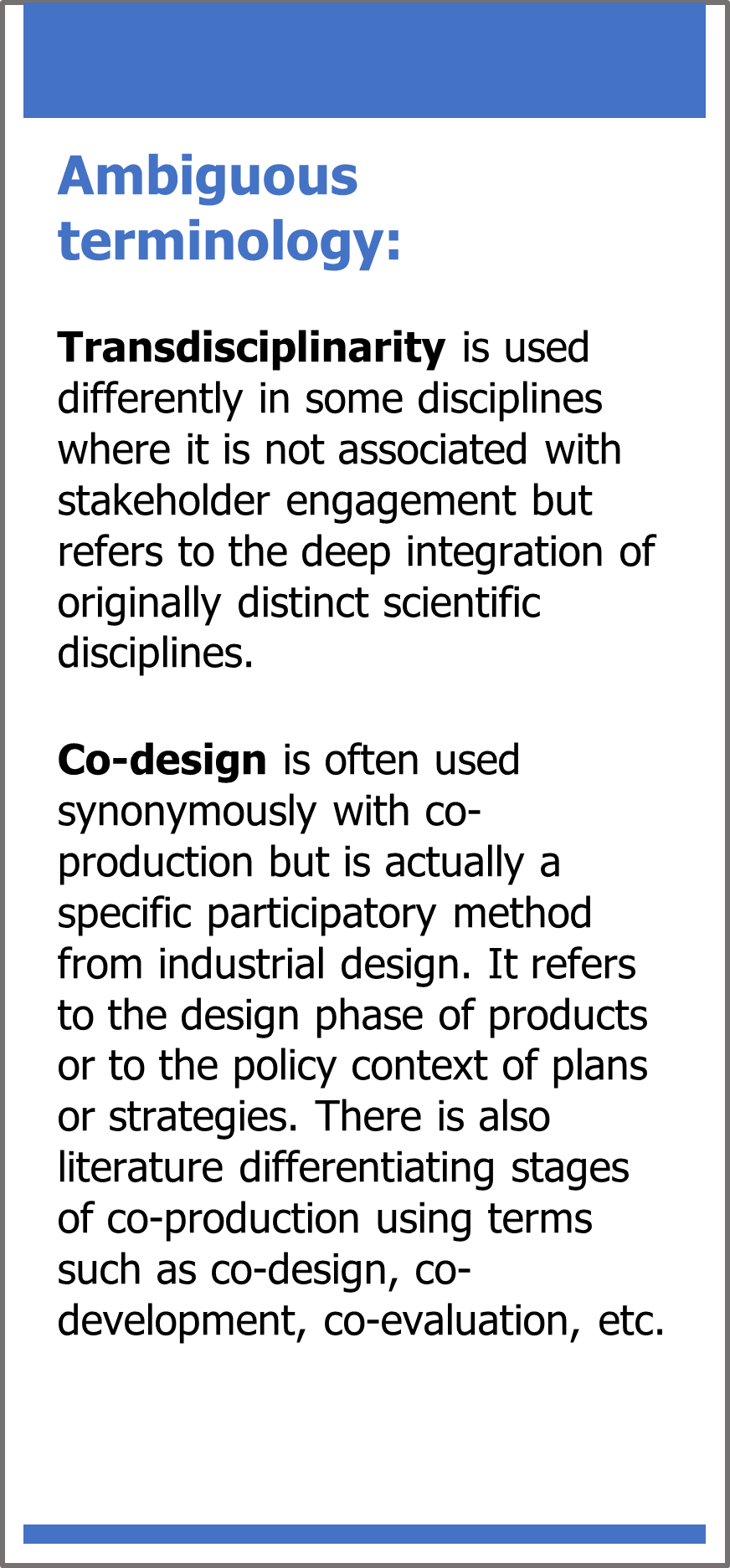

We recently kicked off another project where co-production is a visible element of the proposal, but the requirements for co-producing knowledge in this project have been thoroughly underestimated even by those who wrote it. I dare say, we have all experienced an increasing demand to engage with stakeholders, to co-produce, -create, -design, or -develop, or to design a transdisciplinary research process. This is good, as it caters to the need to diversify knowledge and to consider social discourses. Both elements are crucial to actionable research on issues associated with high impacts, deep uncertainties, and a plethora of solutions, most of which are contested. While the focus on co-production is welcome, it can have disadvantageous effects when the respective terminology is reduced to buzzwords and engagement in research projects remains sidelined.

The IIASA Strategic Initiative fairSTREAM set out to better organize capacities for stakeholder work and co-production of knowledge at IIASA to adequately navigate the associated communication challenges. We are revisiting existing research processes and participatory methods used at IIASA to explore if and when co-production and transdisciplinarity have been achieved or can be achieved, how these methods analyze systems and foster systems thinking, and their capacity to assess justice.

Based on our work so far, I would like to share this brief guidance note to help colleagues choose the right terminology for research proposals to achieve the correct and most adequate form of stakeholder engagement. It is important to note here that we do not claim to have the ultimate definitions for these terms, rather, we support serviceable and distinct ones, including considerations for alternative disciplinary views.

Stakeholder engagement and participation is the best-known and broadest terminology, and without any further specification does not say anything about whether knowledge is co-produced or whether research is transdisciplinary. There are some very useful categories in the literature designed around the information flow between stakeholders and researchers, which help to specify the type of stakeholder engagement a research project entails. These include engagement types that draw heavily on data elicited from stakeholders in focus-groups through interviews and expert elicitation, but also through apps that crowdsource information, for example, on land-use types or high-risk areas (also known as citizen science).

Other types of engagement serve to share results with stakeholders, so the information flow is directed from the researchers to stakeholders, hoping that scientific knowledge will find its way into decision making at a specific level of governance. This happens most often at conferences or in workshop settings. In such workshops, the information flow often goes both ways – researchers present their work, and stakeholders share their knowledge. These types of workshops sometimes feel like a series of presentations followed by a questions and answers session, rather than spaces where work is being done.

The term co-production itself refers to a participatory process in which knowledge is co-produced, when the following criteria are fulfilled:

- co-production is context-based – this goes beyond being local and refers to contextualization with respect to restricting the issues at stake, understanding their emergence, and using appropriate language and terminology.

- co-production is pluralistic as it explicitly recognizes “the multiple ways of knowing and doing” involving multiple disciplines, sectors, and social strata. This may increase transaction costs considerably.

- co-production is iterative in that it “allows for ongoing learning among actors, active engagement and frequent interactions”.

Co-production thus always involves careful stakeholder mapping, even if only one event is designed with the aim to co-produce knowledge.

This also means that most participatory methods can serve co-production purposes if stakeholder selection and event facilitation is organized appropriately. In the fairSTREAM toolkit, we collected participatory methods that have been used to co-produce knowledge at IIASA. This toolkit is an ongoing project, and we will continue to add more methods and connect more research groups across IIASA.

Transdisciplinary research in the context of stakeholder engagement is closely related to co-production. Indeed, co-production is an essential feature of transdisciplinary research and sometimes the terms are used interchangeably. In fairSTREAM, we distinguish the two ideas by using co-production for specific methods, and transdisciplinary to describe entire research processes, thus the difference lies in the scope. A transdisciplinary research project then is a comprehensive stakeholder engagement process spanning the entire project, ideally already starting ahead of, or at the proposal stage and employing co-production measures throughout the project, including reflection and evaluation with stakeholders.

In fairSTREAM, we advance capacities to co-produce knowledge and design transdisciplinary research projects at IIASA. This is particularly appropriate, for example, when questions of justice are at stake, or to understand divers framings of complex problems such as those surrounding nexus issues and climate change. However, we also caution both researchers and funders in the inflationary use of the terminology. Not every project can or should be transdisciplinary, not every event has to co-produce knowledge, but when it is done, it should be done well and with sufficient resources. The fairSTREAM toolkit provides guidance on how to implement participatory methods in a way that enables knowledge co-production.

References:

Norström, A.V., et al. (2020). Principles for Knowledge Co-Production in Sustainability Research. Nature Sustainability 3(3): 182–90.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the IIASA blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.