Everybody’s talking about ChatGPT. The artificial intelligence chatbot, developed by private company OpenAI, allows a user to generate content. It can create poems, articles, short stories, and even jokes. How can researchers benefit from this seemingly revolutionary tool? And why has it sparked controversies, particularly among the scientific community?

ChatGPT: What’s so special about it?

According to Swiss Bank UBS, ChatGPT is the fastest growing consumer app in history. It is estimated to have reached more than 100 million monthly active users since its launch in November 2022. In comparison, it took Tik Tok – the most downloaded app in 2022 – nine months to reach the same number of users.

ChatGPT (generative pre-trained transformer) is powered by a large language model, or LLM, meaning it is programmed to understand human language and generate responses based on large volumes of data. It is (currently) free and easily accessible to the public, however in February 2022 OpenAI introduced “ChatGPT Plus”, a pilot subscription available for US$ 20 per month. It offers faster response times and reliability during peak hours.

Revolutionizing (science) communication

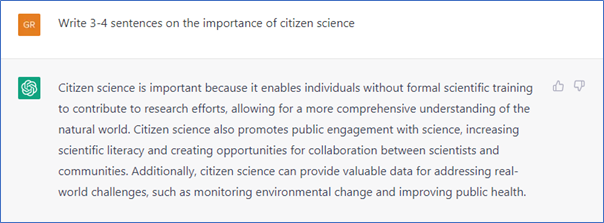

How can ChatGPT help researchers? The options seem endless: the tool can assist with writing emails and researcher biographies. It can simplify complex topics, brainstorm ideas, and improve scientific writing. To demonstrate its abilities, I’ve asked ChatGPT to write a short summary on the importance of citizen science:

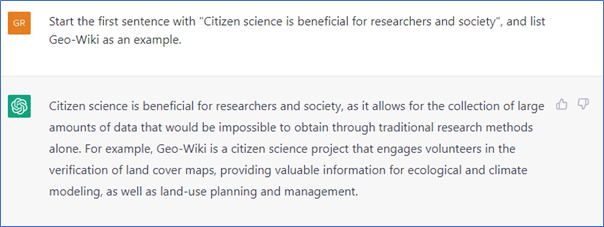

Not bad, right? I think it can be improved, so I’ve asked ChatGPT to change a few things:

With the user’s input, ChatGPT can generate copy on any subject within just a few seconds. It helps speed up the writing process, overcome writer’s block, and untangle complicated topics. Time is precious in the world of research, and with a never-endling list of tasks to complete, ChatGPT seems like a dream come true for busy researchers.

Controversies and risks

A recent Nature article reports that some scientists are already using chatbots as research assistants. The article also refers to ChatGPT as a threat to transparent science: the biggest concern is that students and scientists could pass off LLM-generated text as their own and produce work that is unreliable and inaccurate. Leading science journals have banned ChatGPT as a listed coauthor on papers, however, this doesn’t stop academics using the tool when preparing a text. Inaccuracies could find their way into scientific literature, leading to misinformation and junk science. There is also concern that the chatbot could inadvertently generate offensive, racist, or inappropriate content.

ChatGPT presents a novel problem for academia and education, and has the potential to transform the nature of academic work. In February 2022 it was announced that schoolchildren studying for the International Baccalaureate are allowed to quote from content created by the chatbot, referring to it as an “extraordinary opportunity”. A recent New York Times article suggests to embrace ChatGPT, rather than banning it.

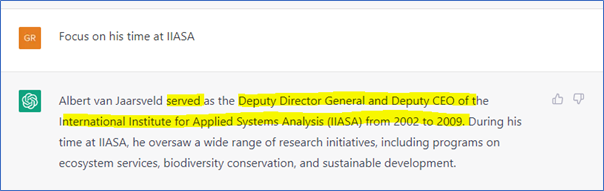

While policies and rules in publishing are frantically being rewritten, one thing is for sure: AI models such as ChatGPT are here to stay. They will continue to evolve, and possibilities will become more apparent. However, (human) eyes for detail and academic ethos are irreplaceable, and technology can only go so far. I’ve asked ChatGPT to write a short biography on (current) IIASA Director General Albert van Jaarsveld, and this is its response:

Albert van Jaarsveld has been IIASA Director General since 2018 – even a quick Google search directs readers to several sources mentioning his current appointment. Despite ChatGPT’s training data being cut off in 2021 (meaning that the chatbot is completely unaware of anything that happened after its training), this simple prompt proves that it doesn’t take much to get ChatGPT to make a factual mistake based on its training data. Suffice to say that providing prompts to ChatGPT on more complex or current topics could open a Pandora’s box of misinformation.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the IIASA blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.