Prompted by a colleague’s question about whether justice is the same as ethics, Elliott Woodhouse sheds light on the nuances of justice as a specific approach to ethics and introduces the IIASA justice framework, a comprehensive tool for systems analysts to integrate justice considerations into their work.

Justice, ethics, or morals?

At a recent conference, I was explaining my work at IIASA to a colleague from another institution, and upon finding that I worked on justice, they asked me: “Is justice the same as ethics?”

This struck me as a revealing question. In the world of systems analysis, we often hear talk about justice, equity, and ethics (often only when we are asked to conduct a dreaded ethics review), but we don’t always stop to think about how these terms relate to each other, how they differ, and what they have in common. In this blog post, I want to provide an entry into thinking about justice as a particular kind of ethical principle, and to introduce the IIASA justice framework, which provides a tool kit for systems analysts to think about how they approach and include considerations of justice in their work.

The simplest explanation of the relationship between ethics and justice is that one is a sub-set of the other. Ethics is usually understood by philosophers to be the discipline that considers questions of ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, and the proper way to act and live one’s life. The study of ethics is the study of these questions at all levels: from how we know the difference between the morally right and morally wrong, the sources of ultimate value they are judged against, and questions of practical decision making. Ethics is somewhat synonymous with morality and they are mostly interchangeable, although ethics has a connotation of being a field of study, and morality sometimes has religious connotations, which cause people to steer away from using it.

Mosaic of the Emperor Justinian.

Justice on the other hand is a particular subset of ethical thinking, particularly one which is concerned with duties and obligations. This has been evident from the very beginnings of discussions of justice. We see it, for instance, in the 5th Century BCE ‘Institutes of Justinian’, which provides a useful definition of justice that stands up to this day:

“Justice is the constant and perpetual will to render to each their due”.

This definition is helpful for thinking about the major distinctions of justice from other kinds of ethical principles. One central feature that makes considerations of justice special is the fact that justice claims are ordinarily thought to be obligatory and enforceable. By way of comparison, other kinds of ethical principles, such as charity, generosity, or mercy are entirely voluntary. No one usually doubts that someone has acted well if they choose to donate to a worthy cause, but almost by definition, a charitable act is a voluntary rather than an obligatory one.1 This is because genuinely charitable/generous/merciful acts are by their nature above and beyond what is expected. Justice, on the other hand, is concerned with the minimum standards of what is owed in order to not breach our moral obligations to others – rendering to each their due. We see this in our language too; we ‘beg’ for mercy but we ‘demand’ justice.

How should we share out limited goods?

Normative or empirical?

Philosophy and the social sciences often have different ways of thinking about what the demands of justice are; philosophy is characterized by having a normative approach, while as social scientists we are often more familiar with the empirical approach.

Empirical approaches to justice attempt to determine whether an action was just or not by asking those involved whether they felt they had been treated fairly. We might ask whether a group had felt fairly represented by a process, or whether it had delivered the outcome they expected. Likewise, we might ask a group what they feel that fair compensation for their losses would be, and check this against what was received in order to determine whether justice was served. Empirical approaches are concerned with what people actually value and what their personal beliefs about justice are. For example, social psychology research has made we publicized advances in understanding how people tend to value justice in procedures over distributive outcomes.

Normative accounts on the other hand, typified by the work of philosophers, attempt to use logical argumentation to determine widely applicable principles (e.g., everyone should have enough for a good life) that could tell us what each person or group should be owed, and use this as a basis to make assessments of whether a decision-making process or distribution of goods is just or not.

To illustrate this: suppose we arrive at a dinner party after the cake has been served, and we want to find out whether it was shared justly. A normative account might try to arrive at an ideally fair principle and check as to whether the distribution we find in the room matches it. We might decide, for instance, as egalitarians, that all present should receive a slice of equal size. We can then go and check whether this pattern of distribution was obtained in reality. The difficulty with this approach is knowing which kind of normative principle to apply. Philosophical questions about what it is we should value (equality, liberty, sufficiency, etc) are famously hard to resolve – and while we can present better or worse arguments in favor of our preferred positions the result is bound to be to a certain extent an arbitrary one.

Conversely an empirical account might conduct a survey of the room to scientifically determine whether those present were satisfied with the slice they received, or whether they felt they had been treated fairly by the distributional process. A potential difficulty here though is that by only investigating whether people feel that justice was served, they run the risk of short-changing people if they are willing to settle for less than what than what a normative account says they might deserve. Perhaps we find that one member of the party received a substantially smaller slice than everyone else, but because of their desperate hunger, or unpopularity with the party, was simply pleased to have received anything at all. By only focusing on perceptions of outcome fairness, we can overlook how injustice can shape our preferences too.

Normative accounts can therefore complement the empirical by providing a point of reference that we can compare empirical findings against. On the other hand, empirical approaches tend to lend themselves better to practical problem solving, and when working on justice problems in the field descending with high-minded ideas about universal moral principles is rarely a helpful approach! Helping systems-analysts identify their own normative assumptions, and make their values explicit in their research was one of the core motivating factors in choosing to develop the IIASA Justice Framework.

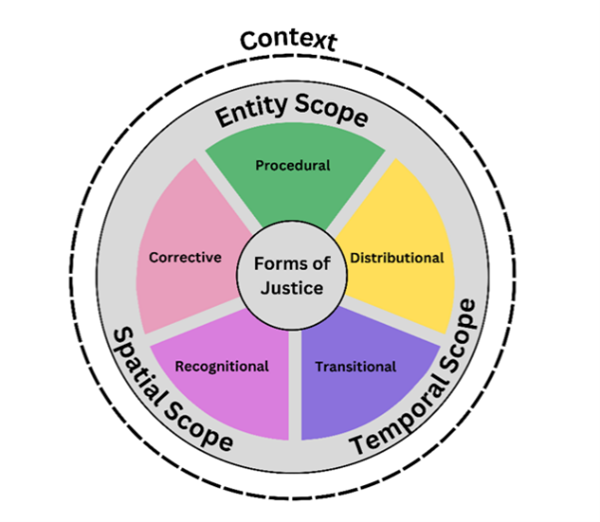

Schematic of the IIASA Justice Framework.

The IIASA Justice Framework

At IIASA, the Equity and Justice Research Group, in collaboration with colleagues from across the Institute and particularly the JustTrans4All and fairStream Strategic Initiatives, spearheaded the development of a framework to help systems analysts understand with greater clarity the role that justice plays in their work and how to include it in their modeling studies. Justice has become a critical area of systems research, and researchers are increasingly aware that perceptions of injustice are a major barrier to effectively tackling global problems such as the climate and biodiversity crises. The framework considers five forms of Justice: distributional, procedural, corrective, representational, and transitional; and positions them within scope and context considerations.

The framework is intended to provide an accessible way for researchers to deepen their understanding of the kinds of justice considerations they may encounter or proactively identify, use to address conflicts, and identify and be able to explain their own normative commitments. The framework itself is normatively agnostic. The aim of the work is not to try and tell you what justice is, or which theory of justice is correct. Instead, the framework provides researchers with reference material to make informed judgements about their own beliefs, but also to make explicit the assumptions they may be making without realizing it.

The IIASA Justice Framework can be found online at: https://iiasa.ac.at/models-tools-data/iiasaequ-justice-framework

1 This is by necessity a rather simplified account of the very complicated relationship between justice and charity. See: Buchanen, A., (1987) Justice and Charity. Ethics. Vol. 3. Pp. 558-575.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of the IIASA blog, nor of the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis.